Eritrean Women call for an End to State-Sanctioned Rape

By Andrea Barron

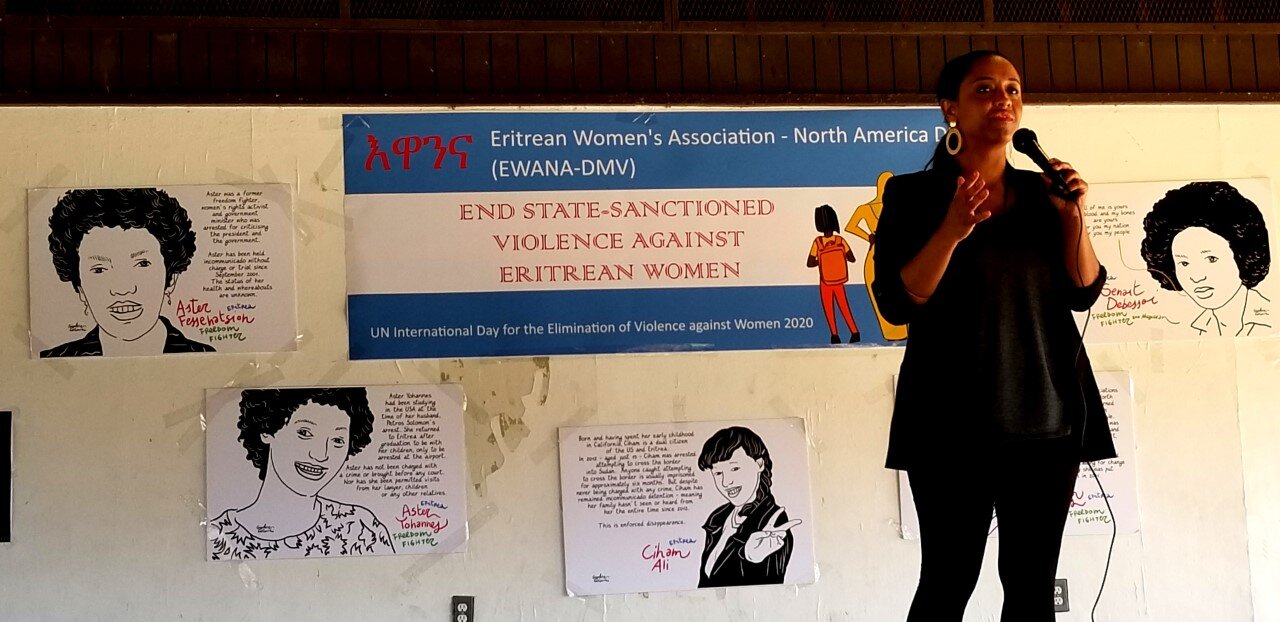

“End state-sanctioned violence against Eritrean Women” declared an enormous banner at an outdoor event held November 28 in Alexandria, Virginia to celebrate the UN’s International Day to Eliminate Violence against Women. The event was organized by the Eritrean Women’s Association-North America and was attended by over 50 Eritreans and a few Americans, myself included. Everybody wore a mask and followed strict social distancing guidelines.

This was the first time the Eritrean diaspora concentrated on gender violence in Eritrea, a tiny country located in the Horn of Africa. Eritrea is known as the “North Korea of Africa” because it is controlled by Isaias Afwerki, a brutal dictator like North Korea’s Kim Jung Un, who has isolated his country from the world. The organizers wanted to call attention to the abduction of Eritrean women like Ciham Ali Abdu, a teenage girl who was “disappeared” by the government after her father defected from Eritrea, and to how this unelected dictator forces young women – and men too--to fight foreign wars.

A major focus of the event was on the systematic rape of young girls and women at a military camp called Sawa, located near the Sudanese border. The government makes every high school student, except married women, undergo 12 months of military training at Sawa while completing their last year of high school. After graduating, the young men and women are conscripted into so-called “national service,” actually a form of “national slavery.” Depending on how well they do on a national exam, they are sent to the army, a vocational program or to college. But wherever these youth are sent, they will remain under government control.

“The Eritrean dictatorship is the worst offender of violence against women,” said Yodit Araya, an Eritrean-American finance professional who helped coordinate this event. “Sixteen year-old girls are removed from their families and become the property of the state. Instead of protecting women from violence in the home or anywhere else, the government itself commits violence against women.”

Just like young men, teenage girls in Sawa are assigned to military commanders. The commanders force the girls to wait on them 12 hours during the day, then often turn them into sexual slaves at night. Africa ExPress quoted a Sawa female graduate named “Lula”: “Everyday, at sunset, the male officers used to enter bossily inside our tents to choose one of us to spend the night with. These officers, although duly married, considered it normal to go to bed every night with a different female soldier. Very soon I got pregnant and as a result I was immediately sent back home.” https://www.africa-express.info/2013/11/27/violence-women-hell-elsa-lula-others-sawa-rape-camp-eritrea

A TASSC survivor from Eritrea verified the practice of state-sanctioned rape in Sawa. “I had a neighbor back in Eritrea,” he said, “who was raped by a soldier there. She got pregnant and lived with her parents and her daughter. Nobody would marry her because of the rape. Her parents let her live with them, but they did not treat her well and neither did anyone else in society.”

The online journal Ethiopia Insight, owned by William Davison, (also a senior analyst for the International Crisis Group) published an article in January 2020 describing what happens to women who refuse sexual relations with Sawa military leaders. The author said these women could be “locked in shipping containers and underground cells, exposed to extremely hot temperatures, beaten, tortured, denied leave, deprived of food and suspended from trees.” www.ethiopia-insight.com/2020/01/15/no-peace-for-eritreas-long-suffering-female-conscripts/

TASSC attorney Angela Edman had many Eritrean female clients before she came to TASSC. Asked if her former clients talked about being sexually assaulted by military commanders, she said: “Yes, some did. Others teared up and said they could not speak about what happened to them at Sawa, what the soldiers did to them or made them do. They would often go into prayer after that.”

Yodit Araya is encouraging more Eritrean rape survivors to speak up about being assaulted at Sawa, but she acknowledges how difficult it is. “They are too ashamed to talk now, but at least we are finally raising the issue publicly with today’s event.”